Flow Water Advocates and commenters oppose Gratiot County CAFO expansion; request public hearing.

Traverse City, Mich. — Flow Water Advocates (“Flow”), on behalf of its thousands of members, is joined by concerned Michigan residents and organizations in filing public comments opposing a NPDES-CAFO Individual Permit for a 3,450-head dairy CAFO expansion proposed by KB Dairy LLC. The proposed expansion is contiguous with and uses the same address as the 8,400-animal De Saegher Dairy in Middleton, Michigan. If approved, the permit would create the largest dairy CAFO in Michigan. Flow and co-signers ask the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) to deny the permit, and hold a local public hearing to facilitate awareness and meaningful public participation.

Support Flow’s work to defend the Great Lakes.

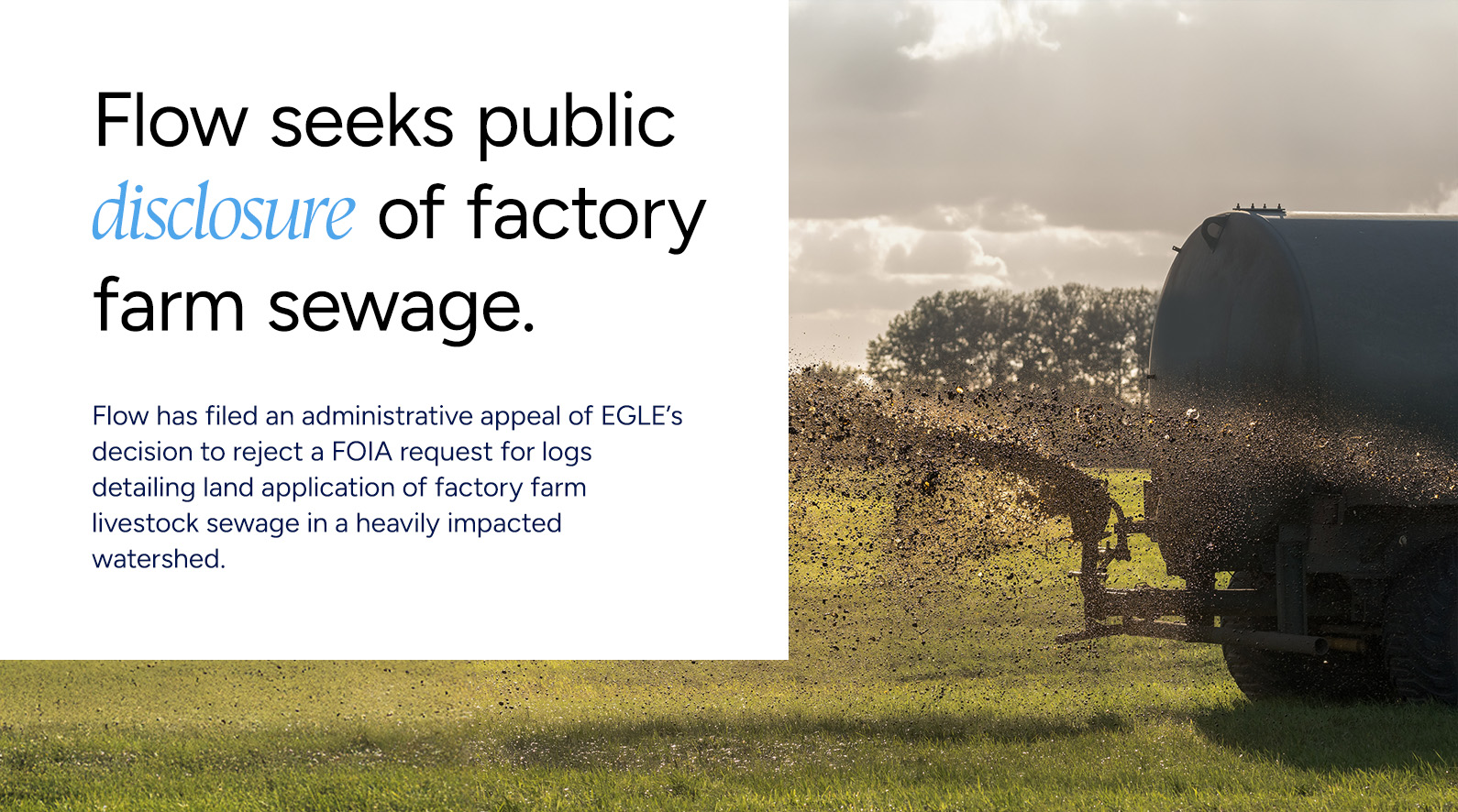

Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), commonly referred to as factory farms, are large livestock facilities that house several hundred to tens of thousands of animals. Gratiot County is home to some of the largest dairy CAFOs in Michigan, and over 400 million gallons of CAFO animal wastes are spread on saturated fields each year — equivalent to the daily sewage generated by Los Angeles County. Dennis Kellogg, a sixth-generation farmer in Gratiot County, describes the CAFO waste management practices:

“When the CAFOs spread their manure, there is required to be a reasonable setback distance from the edge of the field. I’ve noticed they apply right up to the lot lines of residences, businesses, schools, and other public use areas…These facilities are polluting our local communities with excessive amounts of manure, and are not being held accountable for it. Who pays the price for this?“

The comments detail several concerns, including improper separate permitting of the fully contiguous proposed KB Dairy CAFO, which is owned by the same investment corporation as the De Saegher CAFO; failure of the existing De Saegher CAFO to obtain the required groundwater discharge permit; deficiencies in the Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan (CNMP); and the public health threat posed by groundwater contamination in a rural area that relies on private wells for drinking water.

The comments also note EGLE’s obligations under the public trust doctrine and the Michigan Environmental Protection Act (MEPA) to protect Michigan’s water from impairment, for the benefit of all residents.

“These massive livestock operations have contributed to unchecked environmental destruction and soaring cancer rates in other parts of the upper Midwest,” says Carrie La Seur, Legal Director for Flow Water Advocates. “Michiganders take rightful pride in their role as defenders of the Great Lakes. It’s time to take a stand for healthy food, healthy animals, and healthy water.”

Flow is joined in its comments by the Great Lakes Environmental Law Center, farmer Dennis Kellogg, Michigan Farmers Union, Michigan Lakes and Streams Association, Michigan Organic Food & Farm Alliance, Michiganders for a Just Farming System, Progress Michigan, and Socially Responsible Agriculture Project.

###

Flow Water Advocates is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Traverse City, Michigan. Our mission is to ensure the waters of the Great Lakes Basin are healthy, public, and protected for all. With a staff of legal and policy experts, strategic communicators, and community builders, Flow is a trusted resource for Great Lakes advocates. We help communities, businesses, agencies, and governments make informed policy decisions and protect public trust rights to water. Learn more at www.FlowWaterAdvocates.org.

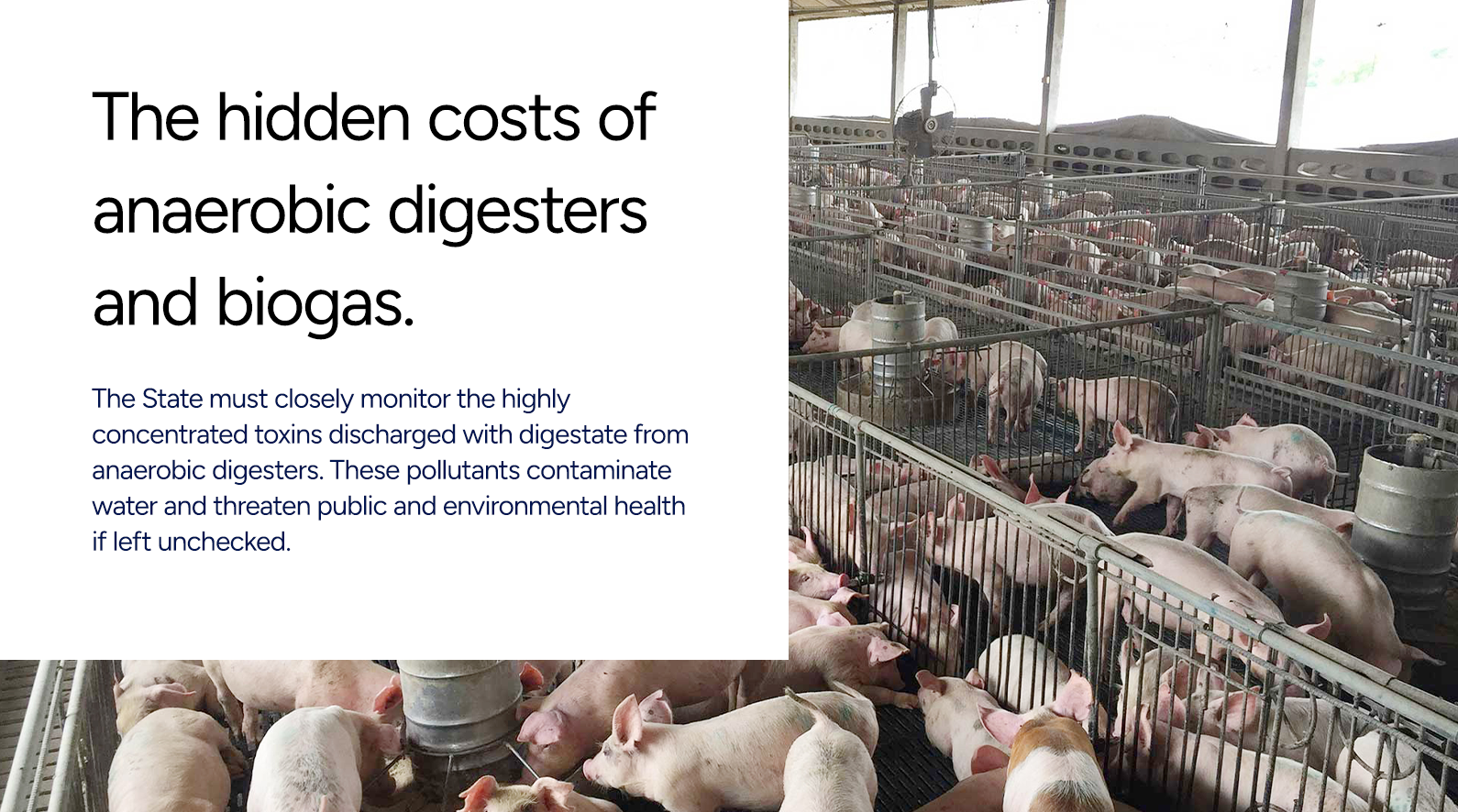

As an environmental lawyer, I’ve also witnessed the insidious creep of industrial agriculture, which disrupts these natural rhythms and threatens the very foundation of our rural communities by replacing careful husbandry with the profitability of volume. Nowhere is this threat more evident than in the rise of the confined animal feeding operation (CAFO), an industrial model of livestock production that undermines the quality of the food we eat every day, while dumping cities’ worth of untreated sewage onto our land and into our water.

As an environmental lawyer, I’ve also witnessed the insidious creep of industrial agriculture, which disrupts these natural rhythms and threatens the very foundation of our rural communities by replacing careful husbandry with the profitability of volume. Nowhere is this threat more evident than in the rise of the confined animal feeding operation (CAFO), an industrial model of livestock production that undermines the quality of the food we eat every day, while dumping cities’ worth of untreated sewage onto our land and into our water.

But we must go further. We must challenge the notion that CAFOs are the only way to produce food. We must support farmers — they’re all around us, please go meet them! — who are raising livestock in a way that respects the land, the animals, and the people who depend on them. We must build a food system that is not only sustainable but also just and equitable.

But we must go further. We must challenge the notion that CAFOs are the only way to produce food. We must support farmers — they’re all around us, please go meet them! — who are raising livestock in a way that respects the land, the animals, and the people who depend on them. We must build a food system that is not only sustainable but also just and equitable.